Path of Fury: Episode I – Tetsuo’s Tower features film VFX tech, the stunt team behind Gladiator 2 and No Time To Die combined with developer Leonard Menchiari’s passion for 1980s martial arts movies and Sega games – it’s kind of wacky, but also very classy.

Leonard Menchiari’s previous game, as a member of Flying Wild Hog, Trek to Yomi, was a to classic Japanese samurai cinema, particularly the films of Akira Kurosawa, and celebrated black and white cinematography.

With Path of Fury Leonard is drawing on Chinese kung fu movies from the 80s, modern martial arts movies like The Raid, directors as well as on-rails arcade cabinets from Sega and Namco, such as Time Crisis. This melting pot of influences is blended and presented in VR and made using Unreal Engine.

The indie dev is tapping into the experience of filmmakers to ensure its VR martial arts hit hard. The team includes art director Mike Galeck, a CG specialist more accustomed to creating award-winning adverts; stuntman Ramón Álvareza; martial arts professional Nacho Serapio and Japanese actor Akihiko Serikawa.

Below I speak to developer Leonard Menchiari about Path of Fury, diving into the cinematic approach, art direction and the challenges of mocap when crafting a film-like martial arts VR game.

Path of Fury: Episode I – Tetsuo’s Tower releases in early 2025, for more details visit the developer’s the Path of Fury website. To follow in Leonard Menchiari’s footsteps, read our guides to the best laptops or game development and best 3D modelling software for the tools you need.

CB: How did you approach choreographing the cinematic martial arts sequences for VR? What were the biggest challenges in making them immersive?

Leonard Menchiari: It wasn’t very easy. At first I just wanted to make a quick workout-type game in which you punched enemies rather than simple bubbles. The evolution into kung-fu and specifically wing-chun felt natural as I dived into production. It felt perfect as a combat style for a game like this: very close enemies, fast paced precise strikes, minimal energy with maximum outcome.

Most of it felt right from the very beginning. Making it immersive at that point wasn’t the real challenge – the real challenge was how to make this whole fight setup approachable and user-friendly without having players wonder why on earth they would have to fight enemies so close to them (without even being able to dodge). Many first time players end up crouching on the floor, being beaten up to death. This is pretty realistic as a natural reaction when you don’t know how to fight.

However, balancing isn’t too tough though: it should be just enough to make you go through the whole experience in a way that feels empowering rather than frustrating and discouraging.

CB: How does the game balance the player’s perspective with cinematic framing?

LM: The cinematic framing was quite straightforward in a game like this. Since there isn’t any exploration, each encounter is like a film-shot. Rather than having a bunch of camera angles, the player would instantly teleport to the next enemy in front of them after defeating the previous one.

I learned this technique from Half-Life Alyx [one of the best VR apps], which brilliantly was able to achieve that immersive feeling of moving through space without having to move your feet. The illusion of movement was given by the intensity of the footsteps sound, and by a simple quick eye blink.

Despite not feeling intuitive or logical at all, in the end it works more than one could imagine. If someone is used to VR they might disagree (since they might be used to moving around with the controller and are now immune to motion sickness), but for most users I believe it’s the best approach to give fast paced immersion with no motion sickness whatsoever. This of course applies for both experts and people who have never used a headset before.

CB: Were there specific martial arts films or choreographers that inspired the game’s visual style or fight design?

LM: Absolutely. Films like The Raid and Ip Man heavily influenced the visual style, especially their fast paced, close-quarters intensity. The focus on efficiency and minimal wasted movement in Wing Chun naturally aligns with these films’ approach to fight choreography.

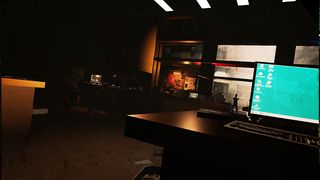

However, while I appreciate the grand spectacle of martial arts cinema, Path of Fury in the end, ended up more like an actual combat training tool. The aesthetic I created owes more to places like the Kowloon Walled City – these dense, organic structures where every space tells a story of survival as a background environment, showing how messed up the world you’re fighting in really is.

On top of that, rather than going in the direction of let’s say Jackie Chan (using a bunch of environment elements in favor of fighting), I decided to go just with your bare fists. This made the approach much more intimate and made the character feel way more resilient. If you make it to the top, it is just because of you, your hands, and how much stamina you actually have in real life.

CB: Did any other video games or VR titles influence your approach to developing this martial arts experience?

LM: Funny enough, not that many. I often noticed how much potential there is in this medium, and how few titles actually take advantage of it. In the end, most of the times I used VR was to either work out, or immerse myself into beautiful environments (a good example of that is Moss).

That’s what I aimed for in the end: something that feels like both a workout and a journey into another world. If there was one that I would say really nailed the way VR should be, that game would be Half-Life Alyx as I mentioned earlier. It’s the best combination of a fun, immersive video game with a film experience in which you are the protagonist and you don’t have a script.

CB: How does the game strike a balance between authentic martial arts representation and the need for accessible, enjoyable gameplay in VR?

LM: The balance comes from focusing on the essence of martial arts rather than full realism. Precision, timing, and efficiency form the core of the combat system, but the mechanics are simplified to ensure accessibility.

Players don’t need prior martial arts experience to enjoy the game; instead, they’ll naturally improve by practicing within the system. It’s designed to reward effort while remaining approachable.

This was really about understanding the core principles of Wing Chun and finding ways to make them naturally accessible through VR. I focused on close combat, fast strikes, and efficient power generation – fundamental aspects that feel intuitive in virtual space.

What’s fascinating is how players ended up often finding themselves absorbing real martial arts principles without even realising it. That to me was both shocking and very satisfying to witness.

CB: What mocap technology or new software did you use and why?

LM: Mocap? Haha, absolutely no way I could use a mocap in something like this. This project is extremely indie, meaning mostly me and some freelancers I hired from around the world. There was no way I could afford spending thousands of dollars for a few minutes of recorded motion capture. I did that with my previous game Trek to Yomi, it was fun working with professional actors and a whole production team, but this is a very different scenario.

I could only manage to get the animations I got thanks to softwares like Cascadeur, which helped me so much getting the physics of the movement right; premade assets from various stores, or free stuff such as Adobe Mixamo animations [read our best animation software guide] and mostly just a mix of animation-blending to achieve variation in each character’s movements and unique poses and actions for each unique event.

If this sounds like magic, it’s because it kinda is. This sort of technology and material wasn’t available even just a couple of years ago, so I can say that I did take advantage of as many new tools as I could to materialise what I had in my head. In the end the results came out almost exactly like what I imagined when I started production, which I still find it hard to believe despite it ending up happening.

CB: What game engine and additional tools are you using to create the game?

LM: Unreal Engine was what I used to create the game. Not easy thing to do, considering that in VR you need to render two 4K resolution images, which requires quite some effort to render, at least 72-90 times per second, on what’s basically a very basic Android device that you’re holding in front of your face (the Meta headset).

The headset is fantastic, don’t get me wrong, but also in order to be that affordable it also means that it’s not the most powerful Android device out there. Developing such a device turned out to be extremely challenging. That’s where Noxnoctis games stepped in during the last month of production and helped me out “optimising” (making the game more light on performance – run faster) and cleaning up the remaining lighting issues we had in the game.

The other main tool was Blender. You can use it for basically everything. And if you don’t know how to use it, just go on YouTube or even ask any AI out there, you will probably end up learning it in no time. We’re in a time where so much can be done, and I’m very grateful to be able to say that I was born in a time like this when it comes to things like these.

CB: Does the game share tech and approaches from the film industry? And how were these implemented?

LM: Unreal Engine as an engine has been used in filmmaking as well, and I think for a good reason: it’s designed to mimic the film-feel, the look and structure of how light goes through the lens and mimics the real-life camera result. This doesn’t mean that if you place something in the scene it’s going to look real of course, but it does make a difference when a software keeps that in mind as a high priority. If you care about achieving a certain vibe, it’s easier to get there this way.

Of course because this game was made for VR, 90% of the effects and filters that I wish I could use had to be removed. I still got to what I wanted more or less, but it was mainly through hacks and cheats instead of a few clicks like it could’ve been if I was making a regular game.

The beauty of film is that you don’t have to deal with any of these technical details, you just place the camera, the subject, and it already looks real – because it is. On the other hand, lighting in filmmaking can be quite challenging (moving cables, generators, power boxes, etc).

In a virtual environment, as long as you’re a bit cautious about performance issues (not putting too many lights or the frame rate will drop), you can place lights wherever you want – which means you have way more control over the way the scene looks.

This allowed me to light every single place the player was teleported to, enhancing the experience and making the darkness one of the protagonists of the experience. Dark, gritty, intimidating environments, fought with extreme speed and power, passing by like a shadow of the world you’re going through.

CB: Are there any groundbreaking features that were critical to its development?

LM: Not really. The simplicity of the gameplay is also its strength. You don’t have to think or focus on too many things, mainly where to hit and in which order. Each enemy has its own unique strike-sequence, which means that instead of spending an eternity in front of each enemy, once you learn the sequence you can defeat them within a few seconds or less.

Increased precision does more damage, more powerful punches do more damage. Fight fast, fight precisely, and you’ll beat the game in no time. If your skills are below average however, you might never reach the top of the tower, nor will you ever get the chance to meet Tetsuo himself.

CB: How do you create retro visual design and style to ensure it feels authentic but also fresh and new?

LM: I think the main difference between actual retro and modern is the amount of details. I love the aesthetic of the late 1990s arcades, and that’s exactly what I wanted for this game. What couldn’t be achieved with PlayStation [original PS1] games or Neo Geo arcade cabinets was the amount of polygons and textures that could be placed in a scene.

Today artists can have a lot more freedom to populate the environments with a huge amount of detail. Why is that important? Because detail is what creates stories. You can imagine that a place around you has been lived and consumed by events that happened way before you even got there, fights and struggles that were overcome and created new layers on top of them. All of this is fascinating to me, and thankfully I was able to focus on it a lot in a project like this one.