Clara Cornish has a background in 2D animation, working at Aardman Animation on movies including Shaun the Sheep Movie: Farmageddon and Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget (read our feature reflecting on a decade of Aardman). She’s also a popular storyboard tutor at Escape Studios, where she passes on her industry knowledge.

We couldn’t resist when offered the chance to get an insight into the current of the industry as well as pass on some advice to any artists looking to get started in animation.

Below I ask Clara about her creative process and how Aardman Animations maintains its unique style, as well as how the stop-motion animation industry has evolved over the years and quiz her on predictions of how AI and other technology could affect the industry.

It’s fascinating to see how this art form is developing, whether that’s the same film technology and processes being used in video games like Harold Halibut or in Aarman’s own Over the Garden Wall anniversary special. Read below for Clara’s insights.

What is your typical process for storyboarding an Aardman film or short? How do you approach translating the script in a visual language?

Clara Cornish: Typically I begin with a brief from the directors, which gives me a detailed explanation of how they foresee a scene will play out. This is in much greater detail than the script, noting character actions, gags and more that need to be included within a scene.

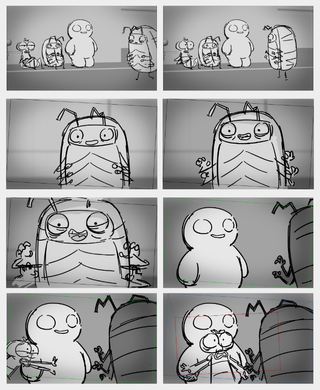

Once I’ve reviewed this in detail, I’ll create a rough thumbnail pass of the scene, sketched out on paper. This allows me to plot out which shots I will use in a clear way, so that I can send it to the Directors for approval. Once they have reviewed and confirmed they agree with the layout, I will create a much more detailed storyboard digitally.

Finally, these storyboards are sent to the editing team to be added into an animatic or reel, which will all help to bring the final product to life!

What is the creative back and forth like between you and the Directors?

CC: There are of course a ton of questions during the process, it’s part of making the magic happen after all! After the brief, I’ll normally ask questions about the specifics of the scene to make sure I’m capturing exactly what they are looking for. Fresh questions tend to come up as I’m working through the storyboard, as I’m able to get a more focused look at each shot.

Depending on the brief, the directors can be very specific about what they want to see and how it should play out, but sometimes it’s much more open to my personal interpretation. Once we’ve completed the first pass of the storyboard, they will send me fixes and tweak requests as the film develops. This helps us adapt the tone, flow and timing of what occurs on the boards to fit with the changing nature of the film. Normally there are many rounds of fixes before the storyboard is complete, so being able to adapt is an important part of the role.

How do you ensure Aardman’s signature style comes through, or is retained, in the storyboards – are there key camera angles, transitions, etc that make an Aardman work?

CC: Interestingly, Aardman’s style is actually quite reserved. We rarely use dramatic visuals or crazy camera angles casually, we tend to save those for important moments so they have a greater impact when it’s their time to shine. Simplicity is our signature, as it really helps the humour land and lets the bigger moments stand out more.

Aardman’s distinctive style comes through its humour and character performances, which we keep as nuanced as possible, avoiding over reliance on obvious or generic performances so every role in the film stands out.

We reflect all of this in the storyboards, as it’s important that they are highly representative of what viewers can expect in the final version of the film.

What are the challenges faced when storyboarding a stop-motion animation versus 2D or 3D/CGI animation?

CC: My primary experience across my career has been in stop-motion animation, rather than 2D or 3D, so it’s hard to compare and contrast. However, stopmotion does create a very unique set of considerations we must be aware of, such as the limitation of sets and camera movements. Cameras especially require specialised rigging, which means how it will work on set has to be far more considered.

Beyond this, it’s amazing how much work goes into the smaller effects you may not notice as much when working with different mediums. How water and weather effects are integrated into a scene are significantly more complicated, and require a great deal of work to get right.

How have advances in technology, software and processes helped (or hindered) storyboarding?

CC: I’ve not really been in the industry long enough to see a major difference in how things are done, but I know of storyboard artists at other companies who have used a wide variety of technology to aid in their creation of content. Others have even integrated VR tools into the process. For me, this far I’ve stuck to the basics, such as Photoshop and Storyboard Pro, both of which are hugely helpful in my day to day work.

Given how long stop-motion animation can take, is storyboarding even more important, and how detailed does it need to be?

CC: Absolutely, a detailed storyboard is always important, not just for stop-motion, but for animation in general. Being able to work out how things look, move and come together is a major part of creating an efficient production, storyboards also help productions to stick to a budget. The more you know about the creative process in advance, the more control you have over the production as a whole. That’s what storyboards are all about in the end, giving teams a blueprint they need to make important choices.

The level of detail in the storyboard for stop-motion animation is very similar to CG animation. In both cases, the illustrations don’t need to be neat or too refined, but they have to nail down story decisions, pacing and continuity. Across both examples, they are very animated and convey a great deal of motion that are essential cues for Directors.

As new technologies emerge, where do you see the future of animation, and stop-motion animation, heading? Do you see more hybrid techniques emerging?

CC: I personally think that the animation industry is already embracing hybrid techniques and experimenting with a number of different approaches to push the boundaries of film and television for their audiences.

There are many examples of studios that have made this shift successfully, most notably Laika and Aardman, that both introduce CG elements into their work to achieve otherwise impossible shots or to streamline production where needed.

I’m sure we’ll see this trend continue, as when using a hybrid approach creatively, it can really open up what’s possible in animation, creating something both unexpected and exciting.

How will AI affect storyboarding? Is it something that concerns you?

CC: I wouldn’t consider myself an expert in the field, but I personally find it very hard to imagine that AI would effectively replace storyboarding. AI doesn’t demonstrate the capacity for idea generation or creative problem solving, relying more on reformatting existing data. Without original thinking and the ability to adapt to problems, AI can’t meet the very specific needs that storyboarders fulfil.

AI can generate assets but storyboarding isn’t about pretty images. It’s about choosing shots, making the pacing flow, making engaging character performances and ultimately creating an emotion for the audience, which is beyond the scope of AI.

That being said, there is potential that AI could help assist creatives and help to speed up the process of storyboarding if the tools are used as a creative support. By helping to take out repetitive processes like adding tone to images or organising files, in an ideal scenario this could allow for more time to focus on the actual creation of storyboards.

More broadly, is there a benefit to AI in animation, which is a time consuming process?

CC: Personally, I feel that there are ways AI could be used to improve the creation of animation, but how effective it is within this task comes very much down to the creativity of those actually using it. As mentioned, there are many activities and tasks for creatives that do not necessarily require a human touch. This could be correcting seams where the mouth connects to face on stop motion puppets, or colouring the frames of hand drawn animation, as examples.

The more time automation can allow for teams to spend on the creative elements of their roles, the better. Doing so could also help animation to reduce costs, ideally leading to more being made overall, and increasing opportunities for those looking for a career in entertainment. However, this remains to be seen.

What advice would you give new Artists and Animators, and particularly someone who wants to be a Storyboard Artist?

CC: I know everyone says this, but I really do think the most important thing is to have a really strong foundational drawing skill. Anatomy, perspective, composition and more are core elements that will help you throughout your entire career. It doesn’t have to be boring, just make sure you’re drawing from life as much as you can, as this will make a major impact on your output.

Attitude is similarly important. Your portfolio will get you hired, but your attitude and how you conduct yourself will give you many more opportunities in the future, such as being rehired for new projects or being bought onto bigger opportunities. Passion, reliability, following direction and handling criticism are all really important parts of the job. The more you showcase this, the better your prospects will be.

However, it is equally important to value yourself as a person – not just an Artist. You also have to make sure you develop a good work life balance. Give yourself regular breaks, and make sure you have enough time for yourself outside of work so you can always put your best foot forward when you are on the clock. It’s really easy to let the job take over, which can lead to burnout if you aren’t careful. I know personally I didn’t think it was important to maintain the balance, but I learnt over time how essential this is.

Is there any advice particular to stop-motion animation you can pass on?

CC: It is helpful to practise storyboarding with limitations, such as without camera movements or without dialogue, as this would develop creative problem solving skills that are essential for working in the stop motion industry.

What skills, qualities or experience do young Artists need to work at studios like Aardman, and what skills or qualities should they focus on developing?

CC: As mentioned, foundational drawing skills are hugely important, focusing on anatomy, composition, perspective and tone. But when it comes to storyboarding, you’ll need an understanding of acting, camerawork and story pacing to ensure you can pass this onto your artwork. Further to this, you’ll need to be able to draw quickly and clearly, with the ability to simplify your work to boost your efficiency.

A good practice is to attempt storyboarding studies of a wide variety of films, not just animated examples. This will help to prepare you for anything when it comes to storyboarding, and prevent you from restricting your abilities in your training.

Practice working to someone else’s brief and implementing feedback as a large part of the job is understanding and interpreting someone else’s ideas and vision. It’s also good to develop your own creative voice through working on your own storyboard projects to find out what kind of storytelling you are good at.

Love to read more about animation? Then catch with our tutorial on how to turn your illustrations into stop-motion animation and read our guide to the best 2D animation software for what the pros are using.