Breaking into game art and game development can seem daunting, but there’s good insight and advice out there for new starters. Christopher Payton has worked in the video games industry for over 20 years. He was previously director at Unity, head of art at Rebellion, home to the new Duncan Jones’ Rogue Trooper movie, has worked as an artist, art director and is now head of art at new studio Lighthouse Games.

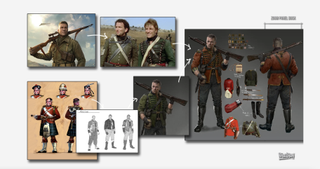

With this track record and experience of working on more than 30 released games, including Aliens vs Predator, the TOCA Race Driver series and most recently the excellent Sniper Elite games, including VR entry and the spin-off Zombie Army titles, who better to ask about the current state of the industry?

First, I ask Christopher for advice on how new artists can get into the industry. “Do what you can to get a foot in the door,” is his answer, and then he elaborates: “This is the single hardest step. You only need a small amount of work examples (three will do) that are well executed, well observed and with a break-down to show your workings. Most applicants are environment artists, but there is always demand for UI and VFX artists which is rarely satisfied.”

Once in the industry, how does career progression look? “For industry progression, always be prepared to fill the vacuum,” reflects Christopher. “That might sound cryptic, but often there are gaps in development of who will handle certain tasks. If you are willing and able to muck-in and help – do. You will increase your knowledge in areas you might not otherwise get exposure to and hopefully your efforts will be recognised.”

One thing I need to ask Christopher is about recent comments from former PlayStation boss Shawn Layden who, as reported by Gamesindustry.biz, said at Gamescom Asia: “AA is gone and that’s a threat to the ecosystem going forward”. This matters because those AA games are often where new artists can enter the industry and gain experience, titles like Unknown 9: Awakening.

Christopher responds, saying: “I think the market has made it difficult for AA games, but I wouldn’t go so far as to say they’ve ‘disappeared’. However, there is a polarisation of games either being top-tier and people paying a premium for these or being incredibly cheap (if not free) at the other end of the scale.”

But he’s also positive: “If anything, I’d say the lower price games, which are often a product of smaller teams using the likes of Unity and Unreal, have enabled a far greater variety of art styles and ideas to emerge and become acceptable.”

Below you can read my full interview with Lighthouse Games’ Christopher Payton, where he discusses his role, trends in game art and more of what you need to know to make it in the video games industry. Also, Lighthouse Games is currently hiring.

How has the role of the Head of Art changed in games, over the years?

Christopher Payton: The role has grown in scale and complexity in proportion with the team sizes we see and the games we make. Art teams are much larger these days with more sub-disciplines, such as dedicated Tech Artists, Animation Implementation, Scanning Art, Material Art, Outsource managers and more. It’s important to know the value of those staff, where and how to hire them, and, like a magic potion, the ratios needed with other artists and supporting roles.

What are the key responsibilities of Head of Art and have they changed?

CP: The role is ultimately responsible for all aspects of art in relation to the project. On large AAA titles such that I’m used to, a lot of this is about building out the right team, with the correct sub-teams to meet the needs of the game and then enabling them to succeed. It’s worth noting that this is separate from a Production role, as a knowledge of Art, Artists and Art pipelines gives vital context to make the right decisions.

What are the most rewarding aspects of working in games, as an artist?

CP: I love the creativity and problem-solving opportunities that my role brings. There are very few jobs where you can bring to life exciting locations, themes or time periods. Also, another huge aspect I love is the team; working with an elite team of character, environment, and concept artists who share the same levels of dedication to making a great product is truly exhilarating.

What have been the most challenging moments, why and how did you overcome them?

CP: There are constant, varied and exciting new challenges in my role, which are often hard to predict, and it’s important to remain positive, level-headed and open-minded when approaching solutions to these.

For example, the reliance on needing to find real-world assets or locations has been interesting, and the process of scanning real-life items to then insert into the game is also a matter of trial and error.

A surprising amount of time is spent researching and trying to find objects to feature in the game, which can sometimes be rare and hard to get a hold of. If the item is particularly unique, we then need to get in touch with the owner of the item and liaise with them to ask permission for us to photograph or scan it – all of this can be quite time consuming for the team!

What are the main trends in game art, in terms of style, realism, technical execution?

CP: I’m not sure if you can call it a trend, but I feel that video games have hit a point of social acceptance where anything goes when it comes to game art. Stylised games, even deliberately low-fi/8-bit games are as equally accepted as high-cost photorealistic games. Just like the music industry is so large that it can accommodate a variety of sub-genres, so too can games and game art.

Do these trends, or expectations from gamers for more realism, affect how a game is made?

CP: For gamers seeking realism, absolutely this affects how the artwork is made; the scientific, fastidious approach to capturing and rendering real-world content is first and foremost an expensive business.

We are constantly balancing and navigating between the desire for greater scope, larger levels, more characters, and additional gameplay elements while working within a finite budget. The Art team often leans on the Tech Art and Engineering teams, which are constantly creating new tools for us to use that can accelerate our capacity to do more with less.

What trend, idea or technology has been the most transformative for art in games?

CP: In the realistic games that I’ve worked on, the use of Lidar and Photogrammetry scanning has had the biggest impact on my work. Being able to capture real-world props, terrain, buildings, foliage and more, and push these into the game has taken the levels of realism up a notch.

That said, it’s still possible to make a subpar level even with high-quality assets, so it’s vital to have artists who know how to design scenes, vistas and narrative dressing work to achieve great results.

How do you see the future of art and 3D art in games evolving, particularly with new real-time engines like Unity and Unreal?

CP: I know from my time working at Unity, and I’m sure the same is true of Unreal, that both are huge advocates of democratising 3D engines and making them available to the wider masses, which is reflected through their pricing models. This approach has and will continue to enable more creators to bring content to their audiences with ease. And these engines aren’t just limited to games; whether it be theatre set designers, architects or historians, all are able to leverage and benefit from these technologies.

The prediction is AI will replace real-time engines in the future, is this possible and how would this affect art direction in games?

CP: It’s hard to imagine AI completely replacing a game engine, given the complexity of real-time engines and the need of them to consistently meet the precise and exact requirements of console hardware in a repeatable way. The more immediate question is if, and how, AI generated content might be used in the current engines – this remains to be seen.

Is AI a threat to new, original ideas and styles or is there room for AI in game art?

CP: Game developers have been using automated and procedural tools for years to accelerate their work and handle repetitive tasks, such as set dressing forests or creating simulated weather systems. When used as an assistive tool to help artists achieve more, AI can be a useful tool.

How do you approach using art to tell a story within a video game?

CP: The starting point is to learn and gather as much information as possible about the game design. In some of the projects I’ve worked on, an author or game writer has been brought in to write a whole pre-story before then proceeding to write the main narrative for the game.

From there, it’s a mix of compiling together mood boards, mind mapping concepts (often scrappy scribbles), and maybe even going on reference trips for real-life experiences to pull on. We will also look at other games, TV shows and films in the same genre to help us pin down colour palettes and overall presentation.

Ultimately, our goal is to create an ‘Art Bible’ that guides all our art teams toward a common goal and unified vision with cohesive artwork.

Could you share an example of how the visual style or environmental design helped shape the narrative in one of your games?

CP: Sniper Elite 5 was notable as it marked the first game in the franchise where we sent artists, designers and a WWII historian to various research locations. The game was originally meant to focus solely on the liberation of France, but we were so wowed by Guernsey in the Channel Islands that we decided to design a whole level dedicated to the Island. The location’s stunning beauty, combined with the duality of being a British territory occupied by the Germans in WWII, provided rich artistic and design opportunities.

How do you see the intersection of art and technology shaping the role of Head of Art, particularly in/using AR and VR, or even AI?

CP: At a day-to-day level, the role is very much human-oriented, relying on a great deal of personal interaction and soft-skills. Building relationships and fostering communication are essential parts of the job. Given this dynamic, it’s difficult to see how AR, VR, or AI could significantly change the core aspects of this role. These technologies may enhance my role and certain processes, but the human element remains irreplaceable.

As games become more technical and take longer to make, how do you prevent drift of ideas and maintain the artistic vision?

CP: The role requires mental discipline to constantly and consistently consider the project from both macro and micro perspectives. For instance, in the same week, we may explore how an individual prop is made as we pay attention to texel resolution, shaders and interaction.

Simultaneously, we may also be looking at concept art and mood-boards for the whole level, paying attention to vistas and lighting. Vitally, you need to keep checking these macro and micro levels to make sure that not only is artistic vision retained, but also that details aren’t missed.

Additionally, I need to also mention the production team here. They play a crucial part of the wider team, making sure that all teams across the board are working on the right tasks against the overall project schedule.

Inspired by Christopher Payton’s insights? The grab one of the best drawing tablets and get creating. Game engines like Game Maker and Godot are also a great place to start fleshing out your ideas.