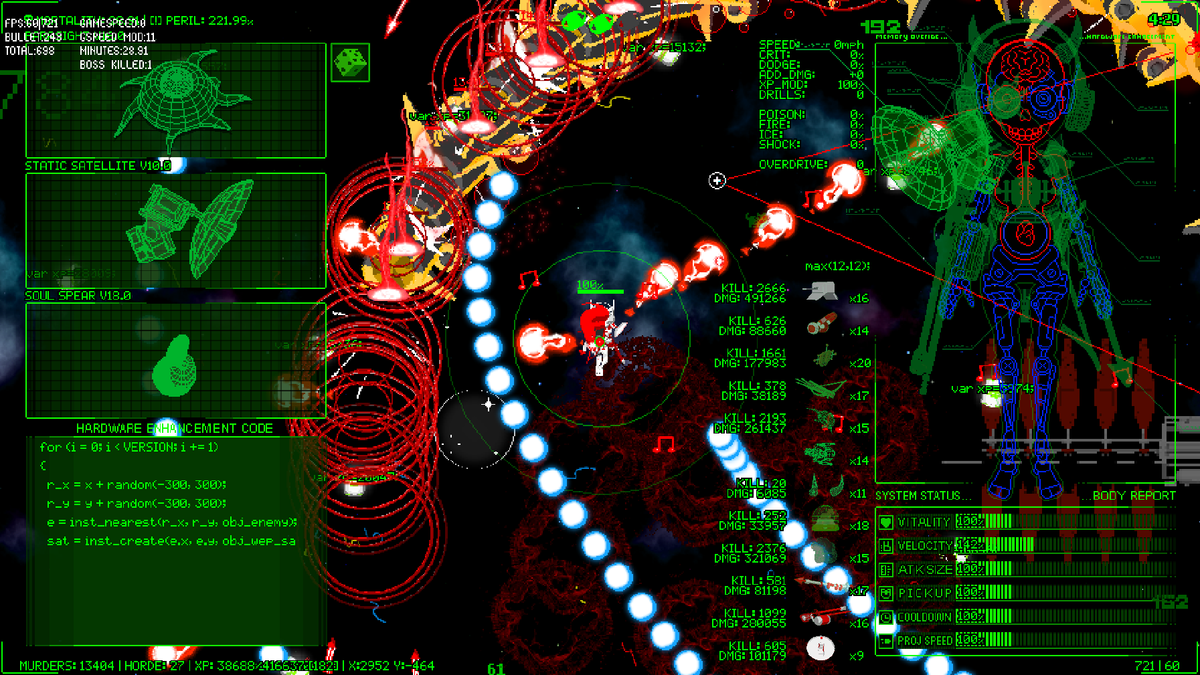

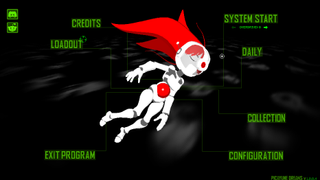

With over 200 entries and after more than 10,000 votes cast in the annual GameMaker showcase, a Picayune Dreams by indie developer Stepford, scooped the winning spot. Voting fans loved the game’s mesmerising and unique roguelike design that blends horde survival with bullet hell gameplay.

The game was made in the GameMaker engine, which streamlines the development process and has proved a perfect entry into game design for many top devs, including Alx Preston for Hyper Light Drifter back in 2016 (read our interview with the dev for its upcoming game, Hyper Light Breaker).

If you’ve not yet tried this game engine, then read our GameMaker explainer, which details all you need to know, as well as our feature GameMaker vs Godot that compares two of leading indie dev platforms.

To peek behind the win, I caught up with Picayune Dreams‘ developer Stepford to discover what makes GameMaker the perfect indie dev game engine, how he grew as a designer and what ‘makes a game, really’ in my interview below.

Congratulations on the win, where did the idea come from?

Andyl4nd, Milky and I had been working together on a few games we made for Newgrounds. Not only were we having lots of fun, but also making some of the best stuff I had ever made. This earned us the attention of our now publisher, Graeme from Two Left Thumbs. He approached us with interest in funding our next game.

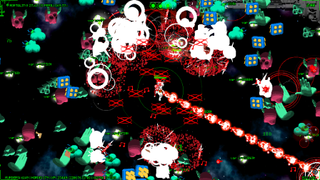

We weren’t too sure what we were going to tackle next, but he suggested an angle in the growing garlic-like genre. Vampire Survivors was something Andy and I had been playing quite a bit, alongside Andy streaming himself playing Touhou in our discord calls. We sort of combined the two and then I took it upon myself to gear it more towards some of the other roguelikes I’ve wasted hundreds of hours in, mechanics like having to defeat a boss to progress forward and a build-focused skill system.

The development of the game took about three times as long as we initially intended, the horde survival genre having been truly wrung dry by the time our release date was announced – but it worked in our favour. People were hungry for something new, the extra development time forced the game in its own direction, one we couldn’t have accomplished with a smaller scope.

What experience do you have of game development?

I have been making games ever since I was in highschool, but my games back then were very crude. In the early days, I would steal sprites from other games and draw over them. Hotline Miami, Spelunky and Zombies Ate My Neighbors were frequent ones, and I’d use them to make shooters that were way outside of my skill set.

I remember one of my friends teasing me about how many projects I would start without finishing them, so to prove him wrong I made a game in a day called Bullet that’s on Gamejolt to this day. It’s a simple game where you jump over bullets, and it used my own original sprites so I felt comfortable uploading it.

The satisfaction of finishing that game helped me finish more of them, as I learned that setting really small deadlines and scopes helped me reach the finish line before burning out or growing bored. I competed in lots of game jams after then, meeting lots of interesting cool people and working on a variety of projects that rapidly expanded my skillset. I’ve been using Gamemaker for about ten years and I think I’ll still be using it ten years from now.

What was the most challenging aspect of creating the game?

I think it was just how long it took. Picayune was by far the longest I had ever worked on anything. The runner up was Olive’s Artventure, and that was only two months of dev time. So going to a year and a half was a huge jump.

There were so many times where I felt like I was wasting my time. It’s a hard feeling to explain, but it was like I was deep under water with no lights or even knowing what way the surface was. I just had to keep swimming in a direction until a light revealed itself, About a third of the way through the game’s development, I hated the damn thing. I thought it was boring, predictable, lame and that when it was finished, it was going to fail. It had been a part of my life for so long that it felt like breathing oxygen.

How can I sell an experience that was as exciting as breathing oxygen, I’d think to myself. I simply didn’t have the experience of working on such a long project, and knowing what I do now, I understand why it felt like that and that it won’t be as bad the next time around.

What inspired the game’s art?

That is mainly thanks to Andyland. He is such a creative and talented guy. I had been a fan of his animations for years and being able to work so closely and become best friends with him isn’t something I could’ve imagined.

His previous animations and art were the base that we applied our influences onto, resulting in a surreal bizarre smorgasbord of taste. Loud music we both liked, abrasive visuals and not being afraid of being edgy at times. There was a lot of bouncing between us.

How did you approach creating the game – do you plan on paper, etc?

The game had a small basic design document that worked as a ‘target’ to shoot at. It detailed a brief story overview, some of the characters, a few upgrades and pickups. It was only four or so pages worth, maybe not even that.

But after that, it was just us working on it every day and adding the things we thought were cool – as well as taking suggestions from a small group of playtesters. We never went back to update the design document because I’ve always felt they worked for a good ‘initial scope’ but become laborious to upkeep when the project reaches that middle point.

Is there an aspect to the game that tested you? What has been the biggest challenge?

Outside of the sheer length of development time being a mental challenge, optimisation was the biggest programming challenge. I want all of the weapons to be able to upgrade infinitely, and I want the runs to be able to go infinitely. It’s a tall ask for any computer, and it should go without saying that the game is intended to break down and lag at a certain point, however I wanted that to be as far in the distance as I could possibly throw it.

There has been a few compromises (like individual XP pickups clumping together to make bigger XP objects) that my greedy self would want to not have to employ, but the game running smoothly is the most important fun factor of the player growing so strong the entire screen is filled with weapons and enemy explosions. Even now, there are a few instances where the game needs to be optimised but I’m hoping to address them in the next update – it’s a never ending battle!

Do you use any other software outside of GameMaker?

I used Unreal Engine and Unity for classes, but my focus has been entirely 2D so GameMaker is the way to go. Audacity for audio editing, OBS for video recording, Sony Vegas for video editing. For any art I do in our projects, I use Aseprite for pixel art and Photopea for anything bigger. I haven’t had to pirate Photoshop thanks to it.

How many games have you made to date, and are you already planning the next one?

Probably around 45-55. It’s hard to keep track because some of them are bigger projects, some are jam games, some are incomplete jam games, some are elaborate jokes, and some are these little single day birthday gifts I’ve made. Really, what is a video game but a screen and a way to make it do a thing!

Right now, I’m preoccupied with the update for Picayune Dreams, and then after that I’m going to be taking a break to help Andy make progress on Endacopia. Then after that, I have some small ideas for our next big game, but they’re pretty faint and I don’t want to make myself too excited haha. I’ve been messing with the Steam multiplayer functionality within the Gamemaker SDK, so it may involve that, but that’s tricky stuff so we’ll have to wait and see.

You can find more about Picayune Dreams and other award-winning games on the GameMaker website, and see more of Stepford’s games at Itch.io.