Last year, I asked half a dozen indie game developers about the pros and cons of using generative AI. Their opinions were mixed: some sung its praises, while others were wary or even dismissive of the technology. But how have their opinions changed over time?

There have been many developments in the fast-moving world of AI since. Artists have filed class-action lawsuits against Google over copyright infringement, Nvidia has launched a number of eye-catching AI tools, from RTX Remix to enable remastering old games to NPCs that react realistically (we even tried and had a conversation with this AI), and improved text-to-3D models have taken off. AI tools have been integrated into software like Adobe Firefly and the launch of AI Copilot laptops is shifting us closer to everyday AI use. It’s been a hectic year.

Against this backdrop and buzz, are indie game developers using AI more or less than a year ago? And what do they think of generative AI now? We ask the same developers and creators and discover how their views have changed.

Leo Dasso, Moonloop Games

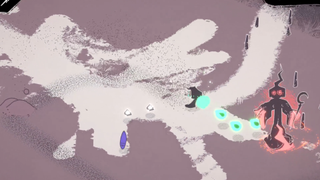

Leo Dasso has been working on the twin-stick shooter / puzzler Hauntii, which has just been released to glowing reviews. When we caught up with him last year, he said that GitHub Copilot offered a valuable way to save time while writing code, but that he was much less enamoured with image-generation tools like Midjourney, declaring: “In their current state they shouldn’t be used for anything, let alone games.”

Nearly a year on, his opinions are broadly the same. “I still use GitHub Copilot to speed up the coding process,” he says, “but I don’t use any image / music / video gen AI.” He adds that although he likes AI coding assistants for the way they can speed up processes and handle some of the more mundane work, such as writing documentation, he says that “they’re still far from perfect, and require a lot of review.”

He also notes that generative AI could become more acceptable in the future. “I see now that there is a plan to build an opt-out system for creators to opt their works out of the training data for gen AI,” he says. “If they actually pull that off, my opinion on it will improve.”

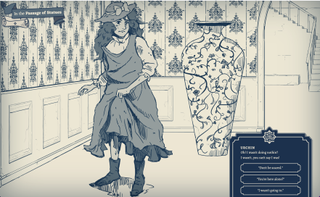

Jon Ingold, Inkle

Inkle has released the acclaimed storytelling adventure game A Highland Song since we last contacted narrative director Jon Ingold, who was scathing of generative AI at the time, declaring it as “no use for anything more specific than a party trick”.

Jon says his views on generative AI haven’t really changed since then – although he has been experimenting with it. “I’ve occasionally tried GPT in tasks,” he says. “When proofreading for typos it flagged false positives, suggested changing the word order to what it actually was, etc. When asking for suggestions of words to fit a certain pattern for a title, it either missed the form or the meaning of the task.”

He has thus concluded that it still “lacks the precision I’d require to trust it with anything.” In addition, he says the results of his attempts at asking GPT questions related to historical research were no more accurate than “going to the local pub and asking around.”

Interestingly, he says that the studio also tried to use AI for translating scripts written in ink, Inkle’s narrative scripting language. “The task was to leave the ink syntax intact but change the words to a target language,” he explains, with the initial target chosen being French, since it was a language he could partially understand and check.

“It performed well at the technical side, at least in short bursts,” he says. “Given more than 300 lines to translate, it would lose the instructions and source text from its context window, and then meaninglessly hallucinate valid-looking ink in French in the rough theme of the game. This is cute to watch, but a disaster from a production point of view, as we can’t be certain where exactly the AI gave up the ghost.” Given the lacklustre results, the studio shelved the experiment after a few hours.

But Jon says he has had some good results with AI. “I have successfully used GPT to write short JavaScript methods, mostly regexes, to perform specific string handling tasks,” he says. “This worked really well – regexes are confusing at best, and tedious to read up on, and the results from the AI were good.”

Then again, he still finds the output of Midjourney “disgusting to look at”, and he has been less than impressed with the IntelliSense coding autocompletion feature that has been added to Microsoft’s Visual Studio, which he says “routinely offers nonsense line completions.” Overall, Jon says that he and Inkle as a whole have been using AI less, with the exception of “short, well-specified algorithms for coding tasks, where it outperforms searching on Stack Overflow.”

Alastair Low, Lowtek Games

Alastair Low is currently working on the 8-bit styled Flea! 2, as well as the ingenious Lowtek Lightbook, a pop-up book game system that uses projection mapping. Last year, he explained to us that he’d been using ChatGPT to generate small pieces of code, but he said he was “steering away” from using generative AI art in his games until the ethical debate around it had reached a consensus on best practice.

He thinks the debate around AI has calmed down since then. “I’ve heard people be more accepting of AI, at least behind closed doors,” he says. “The vocal anti-AI chat online has died down a little on my socials, but has definitely scared most people off about talking about it.”

He adds that he has seen people use generative AI to create concept art to hand over to an art team, as well as for creating a mood board, which he says isn’t much different from grabbing images from Pinterest.

This interesting time during a new art movement

Alastair Low, Lowtek Games

Alastair says he’s using generative AI about as much as he was last year for “improving my workflow and making my life easier”. Chiefly, he’s been using ChatGPT for creating snippets of code, as well as for help writing funding applications, but he has also been using image generation “for fun or inspiration at the mood board stage”.

He’s also been pondering how AI-generated images will eventually come to be viewed in the great, ongoing debate about what is or isn’t art. “I look forward to reading what future art history has to say about this interesting time during a new art movement,” he says.

Dimas Novan Delfiano, Mojiken Studio

Dimas Novan Delfiano is director of A Space for the Unbound, which was recently nominated for the Social Impact Award at the 24th Game Developers Choice Awards. In 2023, he said he had used the Notion AI writing assistant to help create in-game descriptions, and that he would “consider using other AI tools in future as long as the data sets behind them were sourced ethically.”

However, he says he has barely used generative AI in the past year, beyond occasional assistance with correcting grammar. The ethics behind it still worry him. “Some generative AI image tools I know have datasets with ethics and consent issues,” he says, “and to be honest this alerts me whether to use it or not.”

He can see the appeal of using AI to handle repetitive tasks, but his concerns remain. “Using a generator that has questionable dataset consent ethics doesn’t really sit right with me,” he says. “This issue is what makes me refrain as best as I can from using numerous generative AI tools, especially the tools with ethics and consent issues still present.”

He adds that he’s not keen to adopt generative AI into his working practices anytime soon. “I personally still got a lot of enjoyment doing creative work in a traditional digital kind of way,” he says, “and I’m not in a rush to change it too much.”

Matthew Davis, Subset Games

Alongside Justin Ma, Matthew Davis created the acclaimed strategy games FTL and Into the Breach. Last year, he said that Subset Games didn’t currently use any AI tools, but he recognised that generative AI could potentially be a tool that allowed developers on a smaller budget to “create something they could not otherwise”.

He maintains that there is the potential for interesting and valid uses of AI, although most of them “still don’t appeal to me,” he says. Indeed, he thinks AI has limited use cases for the kinds of games he creates: “I’m not looking to generate large amounts of ‘content’ quickly,” he says. “I make smaller games, with smaller scope, and would absolutely prefer a bespoke solution from an actual artist, writer, etc.”

He adds: “I still hope that as the tools improve, they are only used to augment human creativity, rather than replace it. I don’t have a lot of interest in engaging with art, writing, etc. generated by these tools.”

A lot of AI tools are good enough to briefly seem ‘intelligent’ and ‘helpful’, but their flaws are too large to ignore

Matthew Davis, Subset Games

However, he has been experimenting with using GitHub Copilot integrated into Visual Studio as a programming tool. “It could be quite useful for quickly filling in function names, etc. when my memory failed me,” he says. “But I found its capacity to generate a usable block of code not functional enough for me to rely on. I had enough situations where it’s given me something bad that I could not trust it. I would rather write my own code than have to hunt for bugs in an AI’s code.”

Overall, he remains sceptical of the current AI crop. “I think a lot of these AI tools are good enough to briefly seem ‘intelligent’ and ‘helpful’, but their flaws are too large to ignore when used at scale,” he says, echoing Jon Ingold’s findings with AI translation. “And I worry that the people in charge of hiring and firing people won’t notice the smoke and mirrors until it’s too late.”

Alex Rose, Alex Rose Games

Alex Rose specialises in porting indie games to consoles, and he was enthusiastic about the use of AI for generating code when we contacted him last year, suggesting it was like having a senior-level developer around “who you can constantly and unashamedly bother 24/7 until you get the answers”. However, he was less enthusiastic about generative AI art, saying AI tools should be about “removing drudgery” rather than “replacing artistry”.

He says that his viewpoint hasn’t changed since then. “I still feel that the best use for AI is for tools and code to augment professionals with discerning eyes, not to replace them,” he says. “Having new tools that programmers and artists can use to improve their workflow is more interesting to me than trying to replace humans who can clearly follow instructions with models that may or may not be hallucinatory.”

the best use for AI is for tools and code to augment professionals with discerning eyes, not to replace them

Alex Rose, Alex Rose Games

However, he does see how AI could improve things such as real-time rendering. “I think some techniques like Gaussian splatting have shown some real promise, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see the first Myst-style projects or on-rail arcade games integrating it into game engines once it can be performant,” he says. “It’s going to be some years before GPUs are powerful enough for consumer devices to be able to locally run models fast enough to be able to, for example, live-generate skyboxes. So for the time being it’s likely that the impact on the games industry will stay as a few games trying to leverage cloud-based tech, but mostly just used in asset creation.”

Alex recently came second in the long-running Ludum Dare game jam with the Phoenix Wright-like Séance, and he says didn’t see many people using AI to generate assets while he was participating. But he adds that “every other programmer I know” uses code-writing tools like GPT and Copilot, and he still uses GPT regularly to write functions on his website and to help with things like shaders. “It’s simpler to direct GPT to write 200 lines of boilerplate code than to write it myself,” he says.